If you have been diagnosed with lung cancer and have never smoked, it will most likely have come as a tremendous shock. Although smoking cigarettes is the biggest cause of lung cancer, never smokers can get lung cancer too.

Ruth realised that there wasn’t enough information for patients diagnosed with non-smoking lung cancers and that there was a need for more collaboration and research into these types of lung cancers.

We hope that the information provided below will empower you to better understand your diagnosis, the disease and as well as food for thought on questions you could be asking your specialists.

We hope that the information provided below will help you understand that non-smoking lung cancers aren’t rare; give you a better understanding of the possible drivers behind non-smoking lung cancers; and most importantly, offer some guidance on the questions you could ask your oncologist so that you can be given the best possible course of treatment – no matter what stage your cancer is.

With huge thanks to Professor Sanjay Popat, Consultant Thoracic Medical Oncologist at The Royal Marsden Hospital NHS Foundation Trust for helping us put this (hopefully) simple and comprehensive guide together.

We hope it empowers you to ask the right questions, allowing you to understand this complex disease a bit better and ensuring you receive the most effective treatment.

Anyone who has smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime is considered a non-smoker.

We will use two terms to describe those who don’t smoke, and are diagnosed with lung cancer: never smoking lung cancers and non smoking lung cancers. Both meaning the same.

”Understanding cancer & medical terminology can be very confusing. We hope to simplify some of the basic lung cancer terminology here, helping you to understand your diagnosis, enabling you to ask important questions along the way. In case it helps, you can find a downloadable document below on which you can highlight the information you have picked up, and make notes of missing information or add your questions for your next oncologist visit."

Deepa DoshiHead of Mission Services

Smokers and non/never-smokers tend to develop different types of lung cancer. Non-smokers are more likely to have developed a lung cancer as a result of a genetic mutation or abnormality.

A non-smoker is a person who doesn’t currently smoke, but may have smoked 100 or so cigarettes at some point in their life. Never-smokers are considered people who have never smoked or smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Our focus and RSF’s mission centres around those lung cancers not caused by smoking.

Non-smoking lung cancer tumours differ predominantly from smoking-related lung cancer in their origins and drivers behind the cancer.

To determine whether you have lung cancer, your medical team will perform a range of tests such as a chest X-ray, CT scan, biopsy. These tests will help determine what type and sub-type of lung cancer you have and what stage your cancer is. This information helps your oncologist plan your treatment.

Cancer that begins in the lungs is called primary lung cancer. When cancer cells have spread to a patient’s lungs from a cancer that started somewhere else in the body, it’s called secondary lung cancer. This guide is for patient’s diagnosed with a primary lung cancer.

There are two types of lung cancers:

80% of lung cancer diagnoses are called non-small cell lung cancer. In most cases, non-smokers develop non-small cell lung cancer. In the ‘sub-type’ section we will therefore focus on this type of non-smoking lung cancer.

20% of lung cancer diagnoses are called small cell lung cancer and these are extremely rare in non-smokers.

These names, small cell and non-small cell lung cancer, were adopted in the 1960s when oncologists (doctors who diagnose and treat cancer) needed to know which form of lung cancer they were dealing with for treatment purposes. The naming non-small cell lung cancer derived initially from how these tumour cells looked under the microscope – not small vs small cell lung cancer cells.

With 80% of non-smoking lung cancers being non-small cell lung cancers, our focus below will be on the two key sub-types of this cancer type: Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Carcinoma.

About 50% to 60% of lung cancers found in people who never smoked are adenocarcinomas. About 10% to 20% are squamous cell carcinomas.

An adenocarcinoma is a type of cancerous tumour that starts in cells that release substances, like mucus. They are usually found in the outer parts of the lung.

A squamous carcinoma is a type of cancerous tumour that forms in the thin, flat cells lining the inside of the lungs.

Anyone who has smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime is considered a non-smoker.

We will use two terms to describe those who don’t smoke, and are diagnosed with lung cancer: never smoking lung cancers and non smoking lung cancers. Both meaning the same.

Simply put, a patient’s cancer stage is determined by how much cancer you have in your body. Below we have broken it down into simple terms, but more information is available here.

If you have been diagnosed with a small lump in the lungs only (so hasn’t spread), this is called a stage 1 lung cancer.

If you have a small lump in your chest, but some cancer has as well been found in peripheral lymph nodes (lymph nodes “nearby” the cancer), this is called a stage 2 lung cancer.

If you have a lump in your chest, but cancer has as well been found in central lymph nodes (lymph nodes in the middle of the chest), this is called stage 3 lung cancer.

If you have a lump in your chest as well as other parts of the lungs and/or other parts of the body/organs, it’s called stage 4 lung cancer.

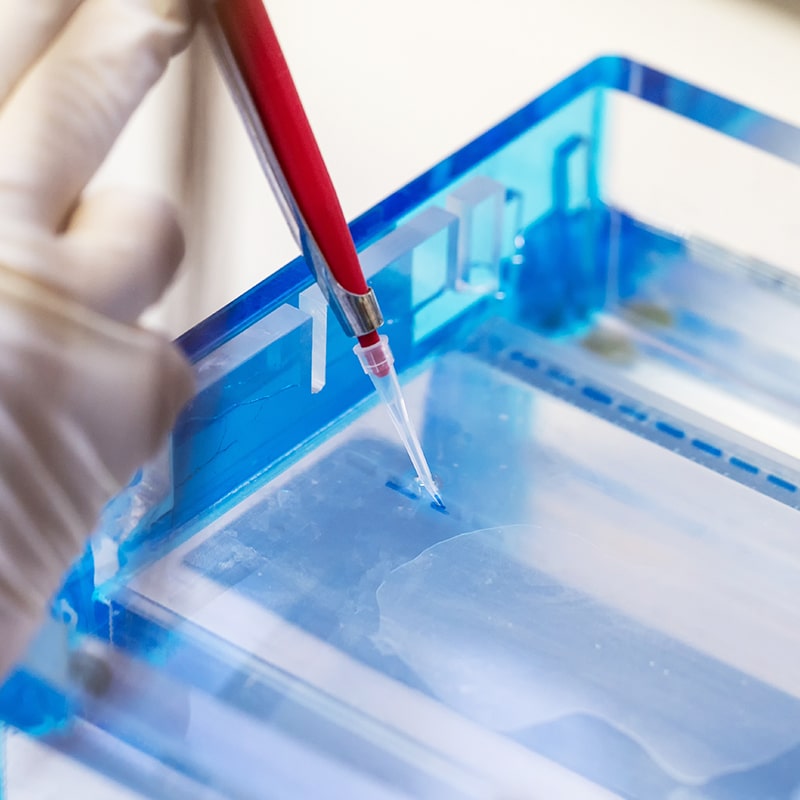

During a biopsy, a doctor removes a small amount of the cancer tissue to examine under a microscope.

”In an ideal world, you are given all the information about your cancer in one go and there is a clear plan of action. Unfortunately, it’s often not so straight forward. To start with, receiving the news that you have cancer will come as an incredible shock, which means that you probably won’t absorb all the details that were shared with you. A second consultation will allow you to ask further questions. In addition, once a cancer diagnosis is made, further steps need to be taken to find out more about your cancer. For non-smoking lung cancers it is vital that a biopsy is taken and send off for molecular testing.”

Professor Sanjay PopatRSF Scientific Advisor

Step 1 of diagnosis is finding out your type, sub-type and stage of your cancer. Step 2 is finding out what the driver is behind your cancer. If this can be determined, a more targeted and tailored treatment plan can be put together for you. All of this information (type, sub-type and driver) can, in most cases, be found by pathologists examining the tumour.

The driver behind non-smoking lung cancers is in most cases a gene mutation or alteration. In simple terms, a change or malfunction in your DNAs building blocks. It is not always possible to find the driver but through comprehensive molecular testing (study of your biopsy), specialists have a better chance of finding out.

Genes are small sections of DNA. Some genes act as instructions to make molecules called proteins. Proteins make up body structures like organs and tissue, as well as control chemical reactions and carry signals between cells. If a cell’s DNA is mutated (a change in a DNA sequence), an abnormal protein may be produced, which can disrupt the body’s usual processes and lead to a disease such as cancer.

It’s these gene alterations which help a cancer grow and spread. Knowing what gene alteration a tumour carries, allows oncologists to better determine what drugs a patient can benefit from. The process of analysing a patient’s genes is called molecular profiling.

Note: it is not the person’s genes (i.e. genetics) that are abnormal but the cancer’s genes that are abnormal. We don’t know what triggers the cancer genes to become abnormal in a never-smoker. Finding causes for these gene alterations is an active area of research.

Molecular profiling has become fundamental not only to inform on a patient’s tumour diagnosis and prognosis (outlook) but most importantly, this unique information can help your oncologist personalise your treatment plan by considering which treatments your cancer is likely to respond to.

A biopsy is when a small piece of the tumour is removed for analysis, to be able to:

1. confirm the cancer type (read more above)

2. identify the abnormal gene behind the cancer

ALK is the name of a protein with the role of telling cells to stop growing. If you have been diagnosed with ALK+ lung cancer, this gene and another gene are broken off and have rearranged, preventing it from its function to stop cells from growing.

ROS1 is the name of a protein that functions in a similar way as the ALK gene. If you have been diagnosed with ROS1+ lung cancer, this gene has fused with a nearby gene. This “drives” abnormal cell growth.

EGFR is the name of a protein that instructs the growth and division of cells. EGFR+ lung cancer means that this gene has mutated (changed), causing the cancer cells to grow and spread.

The RET gene provides instructions for producing a protein that is involved in signalling within cells, and appears essential for the normal development of several kinds of nerve cells. If you have been diagnosed with RET fusion lung cancer, this gene “drives” abnormal cell growth.

The BRAF gene provides instructions for making a protein that helps transmit chemical signals from outside the cell to the cell’s nucleus (its core). BRAF mutations affect the growth, division, specific functions, movement and the self-destruction of cells.

The KRAS gene provides instructions for making a protein which relays signals from outside the cell to the cell’s nucleus (its core). When mutated, KRAS mutations can affect cell division, cell differentiation, and the self-destruction of cells, with the potential to cause normal cells to become cancerous.

Comprehensive genomic testing can determine whether for example an EGFR genemutation or ALK gene mutation is present in your cancer tissue. This vital information will allow an oncologist to set a patient up on the most appropriate & effective treatment course.

– or “tumour genomic profiling”—is a form of testing that classifies tumours based on their genetic make-up to help diagnose and treat cancer. Using a blood test or biopsy, this form of testing examines the genes of cancer cells, looking for mutations (abnormal changes to the build of cells) that have been acquired by these cells.

If you have been diagnosed with lung cancer but no molecular abnormality has been detected, then we advise you to:

”“The genomic abnormality behind your cancer may not be druggable, even if you find out what it is, but at least you know what you are dealing with and a best course of treatment can be prescribed.”

Professor Sanjay PopatRSF Scientific Advisory Group

In 2007 testing started on the EGFR gene. In 2010 this was followed by ALK and ROS1.

Gene testing has evolved significantly over the past 10 years, with tests initially happening in local hospitals or labs. However, in 2018 NHS England decided to centralise all genomic testing into seven Genomic Laboratory Hubs (GLHs) in England, and a Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) was put in place from later 2019, with the aim of providing consistent and fair access to genomic testing. The GMS is a nationally founded laboratory service for cancer patients in England, ensuring equitable access for clinicians and patients across England. There are similar set-ups within laboratories in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Very recently NHS England set up a Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) with the aim of providing consistent and fair access to genomic testing. The GMS will provide a nationally funded laboratory service for cancer patients in England, ensuring equitable access for clinicians and patients across England.

Every patient with a lung cancer diagnosis is meant to have their specimen sent for state-of-the-art comprehensive molecular testing.

Here the NHS is funding the analysis of eight genes, using what is called Next Generation Sequencing Tests.

Comprehensive molecular testing is THE most important thing your doctor can do to find out what the molecular abnormality is that is driving your cancer. It is your right to get your cancer tested for these eight genes.

Finding the driver behind your cancer will allow your oncologist to give you the best possible treatment.

Below we share some general guidance on non-smoking lung cancer treatments. This is to give you some idea of how non-smoking lung cancers in the various stages are treated. However, each patient’s cancer presentation is unique, and a treatment plan will be determined accordingly.

The surgery may need to be followed up with chemotherapy to minimise the risk of relapse (i.e. the cancer returning). And depending on the molecular profile of your cancer, the oncologist may also want to give targeted treatment (often taken as a tablet) to again minimise the risk of the cancer coming back.

For example, in case the abnormal gene detected is the EGFR gene, you might be recommended an EGFR inhibitor tablet, called Osimertinib.

Whereas if your non-smoking lung cancer shows the genetically altered ALK gene, there aretrials ongoing at the moment to see whether an ALK tablet, Alectinib, is useful after surgery.

NOTE: Molecular profiling might not necessarily help you in an immediate way (i.e., there may not be a targeted treatment available), but it might help you be considered for other experimental research or clinical trials that are ongoing.

We are working on sharing more information on non-smoking lung cancer clinical trials with you in the near future.

Treatment often comprises a combination of drugs and therapies, also referred to as modalities. The use of different modalities is called a multi-modality approach.

Here some of the more common treatment combinations used in stage 3:

Often an oncologist will prescribe one year of immunotherapy post the above treatment course, to minimise the risk of a relapse.

However, there is some data that challenges whether the immunotherapies are effective in patients with certain genetic alternations, such as EGFR mutations. Again – knowing your cancer’s molecular profile allows you to discuss with your oncologist whether this is the right treatment pathway for you.

As mentioned earlier, comprehensive molecular profiling also allows a patient to be considered for research trials, with the potential to be considered for new treatments as well.

In a patient diagnosed with Stage IV, understanding the molecular profile of the cancer is extremely important as it can help your oncologist work out which one of the above treatments is right for you. This is the case even for lung cancer in patients with a smoking history.

Patients with a non-smoking lung cancer have a much higher probability of having a genetic alteration in their cancer, compared to patients wo have smoked in their life-time.

If you have been diagnosed with stage IV non-smoking lung cancer, unless it’s really urgent, don’t start with treatment without knowing what the molecular profile is. The way in which the NHS drug funding works, could mean that if you start a treatment, you might be committed to quite a long series of treatment. This could mean that, for example, if you start on treatment “A”, this will only allow you to continue onto treatment “B” or “C”. However, if you didn’t start in the “right way”, sometimes this can impact your treatment options in the future.

”“For never-smoker patients with stage 4 disease I always say we have got to wait for the molecular results to come through. Unless it’s an emergency. In which case we start treatment with chemotherapy. Waiting for the molecular test results to come through will really help us work out what the right treatment for you is and there’s a very high likelihood that you will need molecular targeted therapy (TKI)."

Professor Sanjay PopatRSF Research Advisor

Your valuable donations will go towards vital support for families to help prepare for the death of a parent and raise much needed awareness of non-smoking lung cancers & the importance of its research.

Non-smoking lung cancers are on the rise, with a higher number of incidences amongst women. We are raising awareness of the importance of its research.

We believe that every family facing the death of a parent, should be offered professional emotional support to help prepare for their children’s futures.