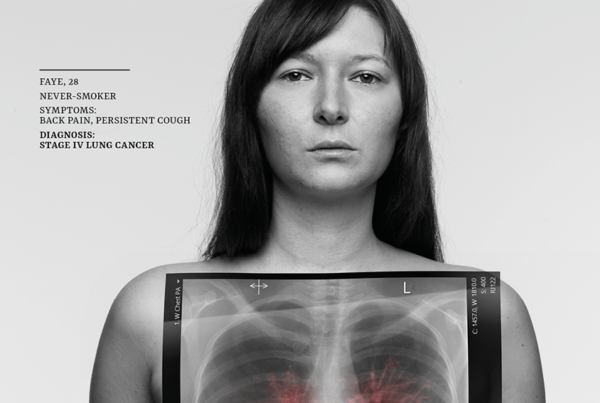

Scientists reveal how air pollution can cause lung cancer in people who have never smoked

There are many unknowns behind many types of cancers, and non-smoking lung cancer is one of them. Scientist found out years ago that the smoking of tobacco had a direct correlation with lung cancers, and hence for years we now find big warning signs on cigarette packages and other tobacco products. What scientists didn’t understand was why people who had never smoked, would develop lung cancers. We know that pollution causes our health harm in many ways, however there has been no evidence to suggest that pollution directly triggers the development and growth of non-smoking lung cancers.

On the 10th of September, Professor Charles Swanton shared some ground-breaking findings of the TRACERx project at this year’s ESMO: European Society for Medical Oncology, with findings showing a direct link with a particular pollutant and EGFR – a particular type of non-smoking lung cancer.

Our Head of Mission Services, Deepa Doshi, shares below a summary of the findings. If you are interested in understanding a bit more about non-smoking lung cancers, the various identified types, diagnosis and treatment, do click on the ‘What are NSLCs’ button below.

If you want to share your experience with non-smoking lung cancer with us, do please get in touch. Our mission to advocate for more awareness, research an collaboration in the field of non-smoking lung cancers start with learnings from patients and healthacre professionals working with lung cancer patients.

What was the TRACERx research looking to understand?

The findings from this research help us understand what causes lung cancer in those who have never smoked and how cancer progresses over time. The research looked specifically at a type of mutation in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) – a protein that instructs the growth and division of cells. EGFR + lung cancers are common in those who have never smoked. It is well known that air pollution causes a range of health problems such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, and dementia. But it was not known how air pollution causes cancers to start. Unlike UV light or smoking which directly causes a DNA mutation which can lead to skin or lung cancer, air pollution does not trigger such a direct genetic change. So researchers looked to better understand the links between air pollution and lung cancers in those who have never smoked. This research is vital as around 15% of all lung cancers are in those who have never smoked and more women than men are affected by this type of lung cancer, and it is on the rise.

What did the researchers do?

This research has been undertaken meticulously over 9 years involving data from 400,000 people with lung cancers across the UK, Taiwan, and South Korea, as well as conducting experiments with mice, human cells, and tissues.

The research involved looking at very fine particles in polluted air, so fine that they are smaller than human hair. The particle is called PM2.5 and is emitted from vehicle exhausts and fossil fuel combustion.

Firstly, the researchers look at data from 400,000 people with lung cancer comparing rates of EGFR mutations in areas with different levels of PM2.5 pollution. The research went on to look at how mice with EGFR lung mutations responded to PM2.5 pollution at levels found in cities.

What did the research find?

Charles Swanton states how this “… study has fundamentally changed how we view lung cancer in people who have never smoked”. The study found higher rates of EGFR mutant lung cancer in people living in areas with higher levels of PM2.5 pollution. These fine particles found in polluted air cause inflammation in the lungs which ‘awakens’ dormant cancer cells that we all have. So, the exposure to PM2.5 pollutants, causes the inflammation which goes on to trigger cells to grow to form cancerous tumours in the lungs. The more exposure to air pollution, the more inflammation is caused in the lungs and this increase the chances of developing lung cancer as a non-smoker. Co-first author and postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute, Dr William Hill, said “Air pollution needs to wake up the right cells, at the right time, for lung cancer to start and grow”. The laboratory studies also showed hope that the body produces an inflammatory protein called interleukin-1 beta (IL1B) when exposed to PM2.5 , and when the IL1B was blacked, this prevented cancers from forming in the mice.

Read more here:

”The funding from the very first RedforRuth day in 2019 was donated to Cancer Research UK and these funds were allocated specifically to the TRACERx project to conduct the research with non-smoking lung cancers.

Dr Sandra StraussSenior Clinical Lecturer & Consultant Medical Oncologist UCLH and RSF Trustee

CRUK PRESS RELEASE 10.09.22: SCIENTISTS REVEAL HOW AIR POLLUTION CAN CAUSE LUNG CANCER IN PEOPLE WHO HAVE NEVER SMOKED

- Air pollution can cause lung cancer in people who have never smokedby waking up cells that carry cancer-causing mutations.

- Experiments in mice show that the awoken cells can go on to form tumours.

- Research pinpoints how people who have never smoked are at risk of lung cancer, opening up new options for prevention and treatment.

Cancer Research UK-funded scientists at the Francis Crick Institute and University College London (UCL) have revealed how air pollution can cause lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

Led by Professor Charles Swanton, the research found that exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5)* in the air promotes the growth of cells in the lungs which carry cancer-causing mutations.

Examining data from over 400,000 people, the scientists also found higher rates of other types of cancer in areas with high levels of PM2.5. They speculate that air pollution could promote the growth of cells carrying cancer-causing mutations elsewhere in the body.

The research was presented by Professor Swanton at the ESMO Congress today (10thSeptember). The research is part of the TRACERx Lung Study, a £14 million programmefunded by Cancer Research UK to understand how lung cancer starts and evolves over time, in the hope of finding new treatments for the disease.

Although smoking remains the biggest risk factor for lung cancer, outdoor air pollution causes roughly 1 in 10 cases of lung cancer in the UK**. An estimated 6,000 people who have never smoked die of lung cancer every year in the UK***, some of which may be due to air pollution exposure. Globally, around 300,000 lung cancer deaths in 2019 were attributed to exposure to PM2.5****.

Lead investigator for the TRACERx Lung study at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL and Cancer Research UK Chief Clinician, Professor Charles Swanton, said:

“Our study has fundamentally changed how we view lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

“Cells with cancer-causing mutations accumulate naturally as we age, but they are normally inactive. We’ve demonstrated that air pollution wakes these cells up in the lungs, encouraging them to grow and potentially form tumours.

“The mechanism we’ve identified could ultimately help us to find better ways to prevent and treat lung cancer in never smokers. If we can stop cells from growing in response to air pollution, we can reduce the risk of lung cancer.”

Air pollution has been linked to variety of health problems, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease and dementia. But how it causes cancer to start in people who have never smoked has been a mystery up to now.

Many environmental agents, such as UV light and tobacco smoke, cause damage to the structure of DNA, creating mutations which cause cancer to start and grow. But no evidence could be found that air pollution directly mutates DNA, so scientists looked for a different explanation.

They investigated the theory that PM2.5****, tiny particles around 3% of the width of a human hair, causes inflammation in the lungs which can lead to cancer. Inflammation wakes up normally inactive cells in the lungs which carry cancer-causing mutations. The combination of cancer-causing mutations and inflammation can trigger these cells to grow uncontrollably, forming tumours.

The scientists examined a type of lung cancer called epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutant lung cancer. Mutations in the EGFR gene are commonly found in lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

They examined data taken from over 400,000 people from the UK and Asian countries, comparing rates of EGFR mutant lung cancer in areas with different levels of PM2.5 pollution. They found higher rates of EGFR mutant lung cancer, as well as higher rates of other types of cancer, in people living in areas with higher levels of PM2.5 pollution.

Co-first author and postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL, Dr Emilia Lim, said:

“According to our analysis, increasing air pollution levels increases the risk of lung cancer, mesothelioma and cancers of the mouth and throat. This finding suggests a broader role for cancers caused by inflammation triggered by a carcinogen like air pollution.

“Even small changes in air pollution levels can affect human health. 99% of the world’s population lives in areas which exceed annual WHO limits for PM2.5, underlining the public health challenges posed by air pollution across the globe.”

The team then exposed mice with cells carrying EGFR mutations in their lungs to air pollution at levels normally found in cities. They found cancers were more likely to start from cells carrying EGFR mutations, compared with those mice not exposed to air pollution. The researchers showed that blocking a molecule called IL-1β, which normally causes inflammation and is released in response to PM2.5 exposure, prevents cancers from forming in these mice.

The research team think that the model presented in their study could be responsible for the early stages of many different types of cancer, where environmental triggers awaken cells carrying cancer-causing mutations in different parts of the body.

Co-first author and postdoctoral researcher at the Francis Crick Institute, Dr William Hill, said:

“Air pollution needs to wake up the right cells, at the right time, for lung cancer to start and grow.

“EGFR mutations are an essential step towards cancer forming, but they are rare, affecting around 1 in 600,000 cells in the lung. These rare cells are dormant until a trigger, such as air pollution, causes them to start growing.

“The mechanism we’ve identified may explain why there is an increased risk of cancer from air pollution, but the risk is much lower compared to smoking, which mutates DNA directly.

“Finding ways to block or reduce inflammation caused by air pollution would go a long way to reducing the risk of lung cancer in people who have never smoked, as well as urgently reducing people’s overall exposure to air pollution.”

Cancer Research UK’s Chief Executive, Michelle Mitchell, said:

“These findings demonstrate that discovery science, which takes years of painstaking work, is changing our thinking around how cancer develops. Thanks to this research, we now have a much better understanding of the driving forces behind lung cancer in people who have never smoked.

“Only by improving our fundamental understanding of the biology of lung cancer will we be able to offer better diagnosis and treatment, regardless of whether someone’s lung cancer is caused by smoking, air pollution or something else.

“It’s important to stress that smoking remains the biggest cause of lung cancer, responsible for around 7 in 10 lung cancers in the UK. Governments across the UK must do more to prevent lung cancers caused by smoking. They must introduce bold action to stop young people from starting to smoke, and provide funding for the measures and services needed to help people who smoke to quit.”

The abstract, titled “Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Promotion by Air Pollutants”, will be presented at the ESMO Congress during Presidential Session 1 from 3.30pm-5pm (BST) on Saturday 10th September. The study has been submitted to Nature for publication and is currently undergoing full peer-review. Initial reviewer comments have been positive.